Communicative pressure on caregivers leads to language input that supports children's word learning

Abstract

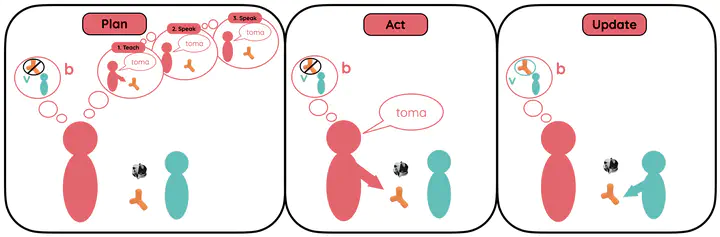

Children do not learn language from passive observation of the world, but from interaction with caregivers motivated to communicate with them. Does this communicative pressure on caregivers lead them to structure children’s linguistic input in a way that facilitates learning? As a case study, we analyze a canonical pedagogical behavior in caregivers: use of ostensive labeling to teach children new words. Using a multi-method approach, we show that this pedagogically supportive behavior can emerge from communicative pressure alone, without any explicit pedagogical goals. First, in a corpus study, we show that caregivers communicate by ostensive labeling precisely when children are likely to learn a new word. In an iterated reference game, we experimentally show that this strategy can arise from pressure to communicate successfully with a less knowledgeable partner. Then, we show that speaker behavior in our experiment can be explained by a rational communication model that includes planning, without any explicit teaching goal. Finally, in a series of simulations, we explore the language learning consequences of having a communicatively-motivated caregiver. We show that under many parameterizations, simple learning mechanisms interacting with a communicatively-motivated partner outperform more powerful learning mechanisms. This perspective offers a first step toward a unifying, formal account of both how linguistic input is structured and how children learn from it.